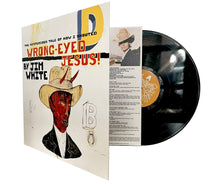

It’s the 25th anniversary of Wrong Eyed-Jesus—the début album from that erstwhile druggie, drifting, storytelling, taxi-driving, recovering Pentecostal maverick talent from Pensacola, Florida who took alt country by storm in the ’90s—and so we’re putting it back out into the world in a beautiful new gatefold jacket.

Tracklist:

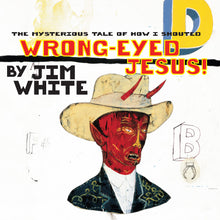

When Jim White’s Luaka Bop debut Wrong-Eyed Jesus appeared in 1997, the unique blend of alt country and metaphysics startled many with its idiosyncratic freshness. It was instantly acclaimed as a classic of the newly burgeoning “sadcore” scene, a point which amused the Florida-based songwriter to no end. “For 20 years I’d written these dark little songs, ” he notes dryly, “Every once in a while I’d play them for someone and they’d shout, ‘Stop! That sucks so bad it makes my ears pop!’, then a thing called alt country came along and, boom, all of a sudden everyone’s hollering ‘Jim, you’re a friggin’ genius!’ I mean, what happened???”

No sooner though, did Jim’s slightly warped worldview arrive at the fringes of the fashionable than his personal life went to pieces. “It was paralyzing, being so appreciated and, yet so destitute. I remember, right when this was going on I got a postcard from Rome. Some fan of mine was visiting the Vatican when he heard one of my songs blasting away on a boom box, echoing through the streets of the holy city! I thought ‘damn! There the Pope is tapping his toe along to ‘Wordmule’ and look at me; dead broke, split up with my pregnant girlfriend and living in a borrowed mobile home in rural Florida.”

The song he wrote to chase away his despair was the ebullient ‘Ten Miles To Go On A Nine-Mile Road’ – a bell ringer rife with dark, edgy musings the likes of;

From the splinter in the hand, to the thorn in the heart

to the shotgun to the head

you got no choice but to learn to glean solace from pain

or you’ll end up cynical or dead.

Soon thereafter fortunes changed for Jim, when a triumverate of British sources came to his aid. First, British trip-hop mavens Morcheeba, heard a demo Jim had made of “10 Miles” and promptly volunteered to produce the track. “They understood that I didn’t have the slightest clue as to how to make a living in that oxymoron known as the music business and they offered to help me in any way they could. ” The chemistry was such that they took time out from their own recording schedule to produce several more tracks which form the backbone of Jim’s upcoming release, No Such Place.

Simultaneously Andrew Hale, of Sade and Sweetback fame, stepped forward and generously offered his services and the use of his studio to aid and abet Jim in the recording process. “Andrew Hale is a friggin’ saint!” Jim exclaims. The result of that unlikely collaboration yielded the atmospheric gem “The Wrong Kind of Love”, a luminous, breathy rumination on the nature of romantic fatalism that begins with the exquisite line:

Nothing’s prettier than a pretty girl

digging a heart-shaped hole in the ground…

The final shoe of grace fell for Jim when Chrysalis publishing head, Jeremy Lascelles, upon hearing the Morcheeba produced tracks, offered Jim the much coveted ‘publishing deal’ – an advance of funds sufficient to settle his mountain of debts and prove to his girlfriend and now newborn daughter that he could be a good provider. “There’s a lot of good people out there who’ve helped me get my ducks in a row, and, thanks to their kindnesses, for the time being anyway, me and my little family have given the slip to them spooks that’ve dogged me all my life.”

As a child Jim was the last of five kids, born late to an itinerant, middle class military family. Conceived on a cross-country journey, he’d traversed the US no less than six times by the tender age of five, when his family put down roots in the muggy, buggy, Jesus-happy backwater of Pensacola, Florida. “This is one hell of a churchy town.” Jim notes. A fact confirmed by statistics recognizing Pensacola as the leader in the United States in density of churches per capita.

Of his inevitable experience in the church Jim recalls, “I’d got messed up with drugs real young and saw my friends get all hollowed eyed and dead looking, so I figured , if I was going to be strung out, it might as well be on Jesus.” But ever the outsider, the church was a poor fit for Jim’s quirky, irreverent character. ” I thought it would be easy, you know, close your eyes and fall into the arms of the Lord, but no matter how hard I tried to embrace it all,” speaking of his experiences with fundamentalist Christianity, “the end times prophecy, the miraculous healing, the whole maghilla, I never could quite get up to speed. I failed miserably every time I tried talking in tongues, or performing miracles. I just couldn’t cut the Jesus mustard. “

Listening to Jim recite the litany of his checkered past is often a study in bewildering contradictions. Inevitably, the ups and downs converge, then become redefined, tragedies being parlayed into blessings and vice versa. Case in point: Jim claims the best thing that ever happened to his music was every musician’s nightmare – getting the fingers on his fretting hand mangled in an industrial accident. “I took a job building chaise lounges . . . walked over to this table saw and before you could say ‘boo’, they were loading me into an ambulance, three fingers on my fretting hand looking like hamburger meat.” But ever the mythmaker, Jim parlayed that horror into a tidy little moral tale. “Sometimes limitations are assets, and likewise in reverse. Before I got mangled I was a real facile guitar player, “chord happy” I’d call it, confused and conflicted by my ability. But after I got all the pins and stitches out, and I learned how to play open chords and fret with just one finger, lo and behold, for the first time in my life what I was playing sounded right.”

Steeped in the influence of Flannery O’Connor and Tom Waits, the album Wrong-Eyed Jesus revealed Jim White as a spiritual anatomist of the American South. No Such Place ups the ante revealing a broader, more diverse collection of songs about rage and redemption, depravity and dreams, dead cars and broken hearts. With tracks produced by Morcheeba, Sade co-founder Andrew Hale, and Q-Burns Abstract Message, along with stellar remixes by Japanese underground guru, Sohichiro Suzuki of World Standard and Yellow Magic Orchestra fame, Jim finds himself reveling in the unlikely zeitgeist of the new album. “This is a crackpot love letter to all those lost souls out there like me who won’t settle for wrong, but have no clue how to get to right.”